Victoria Woodhull

Victoria Woodhull

IN THE month when the United States of America may elect a woman as its president for the first time in its history – see following pages for more on that topic – I felt it appropriate to recall the life of a colourful female who nursed similar ambitions 144 years ago.

Her name was Victoria Woodhull and she was rightly famous in the 19th-century for a variety of reasons – not all of them virtuous.

What is beyond doubt is her extraordinary gift for oratory. It first caught the public imagination in 1871 when she spoke before the House Judiciary Committee on women’s rights.

A year later, dressed in black silk, she took to the stage at the Apollo Hall in New York City, having been introduced by a speaker who had denounced the corruption of both Republicans and Democrats, and received a rapturous reception.

Her rousing address demanding change soon had her audience on its feet and one delegate yelled above the rest that he nominated her for president – a suggestion that received a five-minute standing ovation from the gathering.

It was far from an empty gesture. A month later the spontaneous reaction to her speech resulted in her selection as a presidential nominee by the Equal Rights Party, making history. She became the first woman to be honoured in this way, almost half a century before women’s suffrage was accepted nationally in the United States.

But that’s where the Victoria Woodhull story takes an unexpected turn. She never envisaged she would gain high office in male-dominated Washington, but any political ambitions she may have had were quickly destroyed when she and her sister, Tennessee, were thrown into jail.

That was just the latest twist in an astonishing life that began in poverty and cruelty, progressed through a period when Victoria and her sister made a living as healers and mediums, holding séances and telling fortunes, and saw her marry three times – the first at the age of 15 to Canning Woodhull. It culminated with the sisters encountering – or targetting – Cornelius Vanderbilt, one of America’s richest men.

It has been suggested that they used “their otherworldly connections” to advise him on stock tips. But perhaps they were just astute businesswomen. Whatever the source of their predictions, association with Vanderbilt enabled them to play the stock market and cash in on the financial panic of 1869’s Black Friday.

They claimed to have amassed a fortune of US$700,000, worth many millions in today’s currency, enabling them to start an investment company, Woodhull Claflin & Co, becoming Wall Street’s first female stockbrokers.

Victoria used the power and influence that came with her new wealth to proclaim her belief in women’s rights and reinforce her candidacy for president. She did this effectively – too effectively, perhaps – by launching a radical publication, the Woodhull and Claflin’s Weekly, as a vehicle for her views on a variety of activist topics.

It published, for example, the first English translation of Karl Marx’s The Communist Manifesto. The free thinking sisters also expressed their opinions on social reforms, sexuality, birth control and free love. They were ahead of their time, and it was soon to be their undoing.

Five days before Election Day in 1872, Victoria and Tennessee published a story about a prominent preacher, Henry Beecher, who they alleged was engaged in an adulterous affair with one of his parishioners. They explained that they were revealing the story because of the sexual double standards held against women.

Beecher’s sisters, it transpired, had previously attacked the publication for its views on free love. One subsequently described Victoria as “a vile jailbird” and an “impudent witch”.

Even worse, Tennessee wrote a piece naming a Wall Street banker, Luther Challis, and a friend who she accused of seducing two schoolgirls. Her graphic description of how he took her virginity caused a storm of protest.

Victoria and her sister were accused of obscenity and libel and thrown into jail, where they languished while the rest of the country celebrated the re-election of Ulysses S. Grant, leader of the Radical Republicans, as US President.

|

|

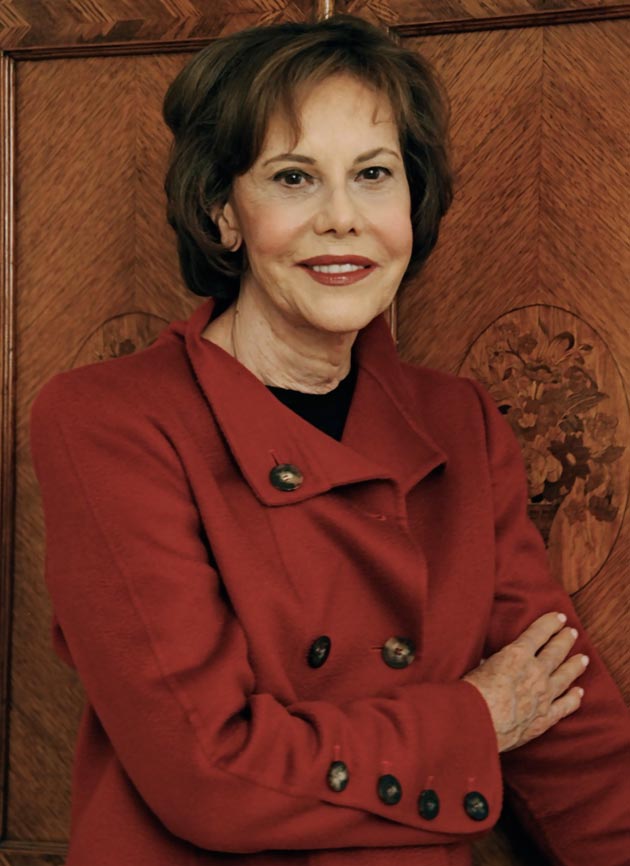

Barbara Goldsmith wrote an impressive

biography of Victoria

|

|

Although they were acquitted six month later, it took its toll. Beecher’s trial for adultery lasted two years, ending with a hung jury, by which time Victoria and her sister were poor once more.

In 1876 their publication folded and Victoria went to London to give lectures, meeting and marrying a banker, John Biddulph Martin, in the process. She then presided over his London estate and a Portuguese castle. But she still entertained presidential ambitions.

Her second attempt at nomination, in 1884, failed but a third, eight years later, resulted in her securing a nomination by the National Women Suffragists’ Nominating Convention. Once again, she had the White House in her sights, even giving herself the title “Future Presidentess”.

But it was not to be. The British Daily Mail declared she was not fit to be America’s president and dished the dirt on Victoria, her sister and the rest of her crazy family. Its allegations included their one-eyed father, a conman, and the fact that Tennessee had been involved in his “cancer centre” scam. There was even talk of blackmail and prostitution.

Victoria had no option but to drop her candidacy and spend the rest of her life quietly in England. She focused her energy on writing, editing and publishing a magazine, The Humanitarian, with her daughter for nine years. Her books included Human Body: The Temple of God.

Victoria died on 9 June, 1927, and is buried in Bredon’s Norton, a small Cotswold village.

The best book on her is undoubtedly Other Powers: The Age of Suffrage, Spiritualism and the Scandalous Victoria Woodhull (1998) by celebrated author Barbara Goldsmith, who died in June this year at the age of 85. The New York Times’ reviewer wrote: “You finish it nearly out of breath astonished at the tragic heroism of the flawed character who tried to challenge the American Establishment.”

Had Woodhull made it to the White House, I suspect her presidency would have been even more colourful than either of the current nominees are likely to achieve.